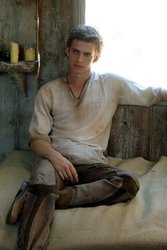

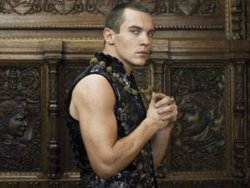

Hard soled boots resounded on the granite floors of the castle hallway as two men, both tall and broad shouldered, strode purposely side by side. One wore the noble ermine mantle of his station around his shoulders. The light grey, speckled fur wafted with each powerful stride, seeming only to be held down by the heavy gold chain about his neck and the amulet of his title hanging from it. His clean shaven, square jaw and the short dark hair above his deeply set, stern gaze made him look more like a knight than a duke, but Duke Ripley Hrothmann of Rochester had set aside his flirtation with sword and shield the day he made Sir Isaak Angevin his Knight General.

He rested a hand on the hilt of his longsword as he walked, and though his jaw was tense and his visage dark, he waited a long moments before replying to the news that he had just been given.

“That’s insane,” he finally said, spitting the words forth like they tasted bitter in his mouth. ”Why would you entertain the idea of allowing the traitor’s whelp into our ranks?”

The duke’s wide jaws tensed at the word ‘traitor’, and he slowed his pace to place a hand on his knight’s shoulder. “Accusations, Isaak. That’s all we have.” His pace slowed to a stop. This was too important to discuss on the move, and he knew that his companion was prone to letting his gut direct his actions, and not the sensibilities of court. He saw the intake of breath and knew that a storm was brewing in the knight's heart.

“We have no proof you mean. Nothing to take to the king. But we know. We know, Ripley!” Sir Isaak stood, facing the other man as their voices rose in the nearly empty hall. Servants diverted their steps to avoid being caught in the sight of either of the men, their hurried feet shuffling away before they could be spotted.

“You know,” Duke Ripley punched a thick finger against the knight’s sternum to accentuate his point. “You know, and that’s good enough for me, but it’s not good enough to bring to the king…”

“So you’re allowing a Lister to join us, as one of my knights?” The hand on his hilt clenched in forced restraint. He wanted to rail against the walls, protest to the heavens, and stop this insanity from occurring. “Why? So this one can do the same thing to our brethren?” He shook his head. "It's insanity."

“You forget yourself, Sir Isaak.” The Duke drew himself up to his full height and peered down his wide nose. “The Angevin Knights belong to King Dunkirk, not to you, and we will do as our liege instructs us.” His lips pressed together firmly as he regarded the knight. When the duke grew irrigated the dimple on is chin and a vein in his forehead made themselves more pronounced, as they did now. “If King Dunkirk instructs me to take in Sir Wilfred’s nephew, then I do so. And if I do so, you will train him just as you have all the others, understand?”

‘His nephew then…’ Sir Isaak mulled this tidbit of information. He knew that his duke did not like the arrangement, but like all men bound by politics and pledges, he had to comply or risk the downfall of all he had achieved. One false rumor, one misspoken word, and a family could be ruined. On the other hand, do something that breaks the rules of your order, and no one cares as long as their pockets remain full. It was the way of the court, not of the battlefield, and he understood his lord had pressures on him that were hidden even from himself. Isaak drew in a deep breath and let it out, resigned to the fact that this would happen regardless of whether it made sense. His hand relaxed on the hilt and he nodded at the duke. “I understand, my lord,” he replied. He did not like it, but he understood it. And he would obey.

Sir Isaak's tongue snaked out to wet his lips as he thought over what this meant for the others who were sent to him for their training. It would be an early introduction to the ways of the court and intrigue, when young knights-to-be needed to focus on warfare and tactics. He didn't enjoy the idea of a coward's kin being allowed to roam about and taint the decent young men who had been entrusted to him, but there was nothing to be done about the matter. The king had decided, and so it would be. “What is the whelp’s name, and when is he arriving?”

Duke Ripley had the good sense not to grin at his knight. “The lad will be arriving in a few days. As for his name?” Now he smirked. “I thought you only addressed them as ‘squire’ until they had earned their name back from you,” he said, turning to resume his path.

Sir Isaak quickly followed him. “You’re right. If he earns his name back.” They continued and turned the corner. ‘If he lasts that long,’ the knight thought to himself, thinking of the late Sir Wilfred, and deciding that if his nephew was anything like he was, he wouldn’t survive a month before fleeing home to his mother and father, begging to be sent to a monastery.

He would run in fear, just as his uncle had done. They were spineless cowards, the lot of them. The sooner he was able to send the whelp running, the better.

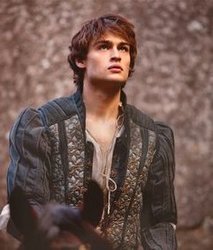

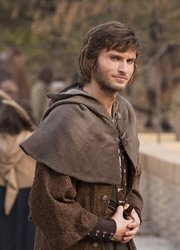

His knight general was slightly smaller than the duke, and many who met him in person were surprised to find out that Sir Angevin wasn’t eight feet tall, with shoulders that brushed both sides of the hall. Although he was but two fingers’ breadth shorter than the duke, his leaner profile made it look as if he was about a third of the other man’s weight. Even so, the way he walked in confidence next to his lord, and the sharp glint in his sapphire sea eyes, left no doubt that the man considered himself his lord’s equal.

Sir Isaak Angevin was dressed in the chain mail commonly worn by knights when not outfitted for war, his lord’s deep green surcoat edged in silver cinched about his waist with a double wound length of deep grey leather. By his side hung an unadorned, well-used longsword, and on his opposite hip laid a matching wide dagger the length of a man’s forearm. His dark brown hair was slightly longer than Duke Ripley’s, as was Isaak’s beard. Its reddish tint hinted at some western blood hailing from the wild sea warriors who sometimes plagued the country’s shore. A straight, strong nose and powerful brows gave him the look of a falcon in hunt, and many said that his charming looks hid a dark and soulless heart.He rested a hand on the hilt of his longsword as he walked, and though his jaw was tense and his visage dark, he waited a long moments before replying to the news that he had just been given.

“That’s insane,” he finally said, spitting the words forth like they tasted bitter in his mouth. ”Why would you entertain the idea of allowing the traitor’s whelp into our ranks?”

The duke’s wide jaws tensed at the word ‘traitor’, and he slowed his pace to place a hand on his knight’s shoulder. “Accusations, Isaak. That’s all we have.” His pace slowed to a stop. This was too important to discuss on the move, and he knew that his companion was prone to letting his gut direct his actions, and not the sensibilities of court. He saw the intake of breath and knew that a storm was brewing in the knight's heart.

“We have no proof you mean. Nothing to take to the king. But we know. We know, Ripley!” Sir Isaak stood, facing the other man as their voices rose in the nearly empty hall. Servants diverted their steps to avoid being caught in the sight of either of the men, their hurried feet shuffling away before they could be spotted.

“You know,” Duke Ripley punched a thick finger against the knight’s sternum to accentuate his point. “You know, and that’s good enough for me, but it’s not good enough to bring to the king…”

“So you’re allowing a Lister to join us, as one of my knights?” The hand on his hilt clenched in forced restraint. He wanted to rail against the walls, protest to the heavens, and stop this insanity from occurring. “Why? So this one can do the same thing to our brethren?” He shook his head. "It's insanity."

“You forget yourself, Sir Isaak.” The Duke drew himself up to his full height and peered down his wide nose. “The Angevin Knights belong to King Dunkirk, not to you, and we will do as our liege instructs us.” His lips pressed together firmly as he regarded the knight. When the duke grew irrigated the dimple on is chin and a vein in his forehead made themselves more pronounced, as they did now. “If King Dunkirk instructs me to take in Sir Wilfred’s nephew, then I do so. And if I do so, you will train him just as you have all the others, understand?”

‘His nephew then…’ Sir Isaak mulled this tidbit of information. He knew that his duke did not like the arrangement, but like all men bound by politics and pledges, he had to comply or risk the downfall of all he had achieved. One false rumor, one misspoken word, and a family could be ruined. On the other hand, do something that breaks the rules of your order, and no one cares as long as their pockets remain full. It was the way of the court, not of the battlefield, and he understood his lord had pressures on him that were hidden even from himself. Isaak drew in a deep breath and let it out, resigned to the fact that this would happen regardless of whether it made sense. His hand relaxed on the hilt and he nodded at the duke. “I understand, my lord,” he replied. He did not like it, but he understood it. And he would obey.

Sir Isaak's tongue snaked out to wet his lips as he thought over what this meant for the others who were sent to him for their training. It would be an early introduction to the ways of the court and intrigue, when young knights-to-be needed to focus on warfare and tactics. He didn't enjoy the idea of a coward's kin being allowed to roam about and taint the decent young men who had been entrusted to him, but there was nothing to be done about the matter. The king had decided, and so it would be. “What is the whelp’s name, and when is he arriving?”

Duke Ripley had the good sense not to grin at his knight. “The lad will be arriving in a few days. As for his name?” Now he smirked. “I thought you only addressed them as ‘squire’ until they had earned their name back from you,” he said, turning to resume his path.

Sir Isaak quickly followed him. “You’re right. If he earns his name back.” They continued and turned the corner. ‘If he lasts that long,’ the knight thought to himself, thinking of the late Sir Wilfred, and deciding that if his nephew was anything like he was, he wouldn’t survive a month before fleeing home to his mother and father, begging to be sent to a monastery.

He would run in fear, just as his uncle had done. They were spineless cowards, the lot of them. The sooner he was able to send the whelp running, the better.

Your support makes Blue Moon possible (Patreon)

Your support makes Blue Moon possible (Patreon)