WeekendAnchor

Turd Ferguson fan account

- Joined

- Oct 17, 2019

- Location

- Central Standard Time

Two years ago, while attending a lecture from Yuri Oganessian, founding synthesizer of many of the ultra-heavy elements on the period table, I was exposed to the idea of Simulation Theory, the idea that our world is a computer simulation of some sort. Two professors sitting behind me in the lecture hall were discussing the usages of particle colliders and one of them brought up the idea that such colliders could be used to observe the behavior of the lowest base components of our universe and to determine if they behave like computer bytes or programming language. Of course, I had seen movies like The Matrix, but this was the first instance I had heard this discussion in an academic setting: the idea of our world being a computer simulation. It got me curious and shortly after that night, I began researching Simulation Theory. My journey since then has led me to the conclusion that it is most likely we live in a computer simulation.

This post isn't an attempt to sway others' opinions or "convert" anybody. If anything this is more of a personal exercise that I hope to make something constructive out of and possibly promote discussion with. Before we begin, I'll disclaim that I am not an expert. In anything. (except maybe masturbating). I studied chemistry for 2 years at a popular state university and now I study accounting. So, if you want to read more about Simulation Theory or share your thoughts/ideas, I'd love to talk, but keep in mind this isn't super-serious and I'm not qualified to explain high-concept math or science concepts.

You can find a lot of discussion on Simulation Theory on the internet but I don't consider it all to be very productive. For example, some of the top posts on the subreddit r/simulationtheory are memes about eating silica packets, paint jobs that makes cars and buildings blend into the environment, and two ceramic busts that look like the meme of the boy following the girl around with a trumpet. Am I wrong for trying to find serious discussion of Simulation Theory on Reddit, or is the public at large simply not interested in entertaining the thought? The answer is probably both, but I don't see why it has to be that way. The document responsible for most Simulation Theory discussion today was published in the journal Philosophical Quarterly in 2003 and outlines the basic argument for why it is more likely than not we live in a simulated universe. You can read the full paper by Nick Bostrom here , but I'll summarize the argument below:

Why are you living in a simulated universe?

Bostrom's paper argues that one of the 4 possibilities must be true:

Scenario 0: Humanity never develops the capability to run hyper-realistic simulations

Ok, I cheated a bit because Bostrom doesn't seriously discuss this scenario, though it is commonly included in modern discussions of Simulation Theory. Simply put, this scenario suggests that it's impossible that any computer ever could fully simulate an entire world with the precision we observe now. Most people agree that this scenario is fairly unlikely. When looking at the strides computing power has taken in the past 20 years alone, it isn't a far cry to think that lifelike global simulations could be possible in the a few decades' time. Moore's Law states that every 18 months, processor speeds double from their capability 1.5 years ago. A processor the same strength as one made 18 months prior will cost half as much to manufacture, according to this rule, and the very cutting edge of computing should quadruple in strength every 3 years. The advent of Quantum Computing may even throw Moore's Law out the window as bytes go from being 1's and 0's to being a value along an entire spectrum, and herald a growth in computing power akin to the industrial revolution's impact on manufacturing technology.

Scenario 1: Humanity is capable of developing simulation technology, but goes extinct before being able to fully utilize it

This possibility gains more and more traction every year as reports of climate change and increasing global conflict grow more frequent. Bostrom, with some humor, devises a formula he calls DOOM to try to quantify the likelihood of scenario 1. He doesn't fully discount this possibility, and even goes as far as to suggest that "mechanical bacteria ... nanobots, designed for malicious ends, could cause the extinction of all life on our planet." Grim, but I like where his heart is at. My money for scenario 1 is on climate change though and if I had to choose another theory for humanity's technological future, the "doomer" in me would say we're likely to go kaput as a species before anything truly amazing happens. Regardless, there's no evidence yet that global extinction is more possible than the alternative, so the logical mind has to move on to another theory.

Scenario 2: Humanity is capable of developing simulation technology, but isn't really interested in using it

Similar to scenario 0, this one is simply not probable. The concept of "convergence" explains why it is much more likely that civilizations would want to run ancestor simulations than not. Looking at the popularity of simulation games like The Sims, a future civilization would have to converge together to be completely unlike us and not find simulated beings interesting. Another possible "convergence" is that the cost of running such simulations would be prohibitively expensive, but between the increasing number of millionaires the money to fund simulations shouldn't be hard to come by. It isn't unreasonable to think that highly advanced simulations could have military applications, and if this type of simulation was quite expensive for some reason, I'm sure America's defense budget could make room for it. On top of this, all it would take is 1 computer to simulate our entire world. Therefore, to completely avoid this hypothetical single computer to run an ancestor simulation, there would have to be a global convergence of culture that would make it unlikely or impossible. Perhaps an advanced civilization has a moral objection to running simulated worlds. Well, even if this were true, this civilization would also need some way to completely outlaw morally objectionable activity.

When you think about cultural convergences as the only reason why an entire global civilization couldn't or wouldn't want to run ancestor simulations, scenario 2 becomes much more unfavorable. There simply isn't a historical precedent to suggest that a future world would converge to one mind set and disagree with something so fundamentally interesting to us now.

Scenario 3: Humanity is capable of developing simulation technology, and uses the hell out of it

Now we get to what Bostrom describes as "conceptually the most intriguing" scenario, and the reason why I'm here typing this out in the first place. Most believers in Simulation Theory say something along the lines of "it's more likely that we live in a simulation than not" or "most evidence that we live in a computer simulation can't be disproven as of yet". If an advanced society became capable of running ultra-realistic simulations, they would create far more simulated worlds than they would have real worlds. Therefore, the most probable reason for any given person's existence would be because they are a simulation, given the raw number of simulated people vs. "real" people. It's important to note that Bostrom ends the paper saying that "In the dark forest of our current ignorance, it seems sensible to apportion one’s credence roughly evenly between" the three main scenarios. If you seriously debate the likelihood that you live in a simulated world, then you must also seriously debate the opposite. The scientific approach doesn't seek to fit the world into a pre-determined idea, but rather formulate ideas that explain why we see what we see. In other words, we look for a box the universe fits into, not to cram the universe into a box we already have. With this in mind, I want to move onto observable and measurable phenomenon that would be explained by Simulation Theory.

You are living in a simulated universe, and why.

The first example I'll give of something that can be explained by Simulation Theory is something many people have become familiar with thanks to high school physics, but I'll give a refresher on just in case you've forgotten

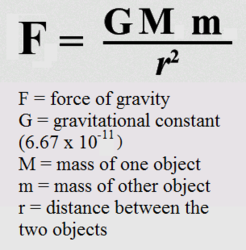

This is the formula for calculating the gravitational pull that 2 objects have on each other:

This is known as an "inverse square law", which basically means the magnitude of the force is determined by the square of the distance between the two relevant objects/bodies. Want to know the gravitational pull between the Sun and Earth? Easy, just calculate their masses and multiply them together, then divide by the distance between them, squared. In order to get a unit of measurement that actually makes sense, the constant G is used so that you end up with Newtons as your unit. According to this formula, your left boob and the planet Jupiter have a gravitational pull on each other, but of course this pull is tiny because the distance between you and Jupiter, "r" in this case, is veeeery large, and the mass of your left boob is veeeery small (m) compared to the mass of Jupiter (M).

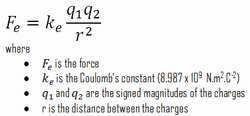

Hopefully you're following along so far. Now I'm going to show you the formula for determining the pull that two charged particles have on each other. Called "Coulomb's Law", this formula can be used to find out how strong of a pull an electron and a proton have on one another, or how strong of a pull two oppositely charged magnets have on each other. Thinking about this law in terms of magnets is actually quite useful for understanding the important difference between Coulomb's Law and gravity. The determining force here is NOT GRAVITY, since the pull that two magnets have on each other is really just decided by their strength and not their size. Two magnets can have a very strong pull but be very small. So we know that the size ("m" or "M") of charged particles is not relevant for deciding how strongly attracted they are. It's really just the magnitude of their charge.

This is Coulomb's Law:

Look familiar?

It's also an inverse square law, just like the force of gravity. But unlike the force of gravity, this equation is used to determine how strong the force is between two charged particles, like electrons. Just like how the pull between planets and physical objects drops off as their distance increases, so too does the force exerted by two charged objects drop off as they move farther away, and at the exact same rate. So why do the planets orbiting the sun and the electrons flowing through your motherboard behave in the same way, despite being compelled by different forces? One solution could be that Coulomb's Law is being used to crudely approximate gravity for us in a simulated world.

Another observable quirk that would be explained by us living in a simulation is Fermi's Paradox. Fermi's Paradox basically states that: if the universe is billions of years old and contains a seemingly-infinite number of planets, then it must also contain a seemingly-infinite number of life-bearing planets. Then why have we not been in contact with any of them? This paradox can be reasonably explained by a number of things, such as the unfathomable distance between our solar system and others coupled with the limitations of traveling near the speed of light. But still, all reasonable calculations result in estimates of interstellar colonization taking significantly shorter time than the current life of the universe. If we lived in a simulated world, there wouldn't necessarily be a need to simulate alien life outside of Earth, especially if we live in a simulation meant to test the hypothetical impact of various global events.

Even at the cutting edge of theoretical physics, the idea of Simulation Theory has taken hold of top academic minds. The 2016 Isaac Asimov Memorial Debate, moderated by Neil DeGrasee Tyson, was centered around the question Do We Live in a Computer Simulation? During this debate, James Gates shares some of the findings of his research. This clip is of Dr. Gates talking about finding error-correcting codes in natural particles while using the Large Hadron Collider. If you understand computer science pretty well, my friends tell me it's pretty interesting, but the jargon is a little too technical for me to fully follow. You can find the full debate here if you have a spare couple hours and want to listen to very smart people talk about this topic at great length.

You live in a simulated universe, but why?

Almost everyone is familiar with the concepts of means, motive, and opportunity in relation to criminal justice. In order to have a slam-dunk prosecution, you need to identify how, why, and when a defendant would have committed a crime. A lot of the casual conversion surrounding Simulation Theory revolves around our world being some sort of computer game. I really don't like this idea for a couple reasons, mostly because the motive doesn't make much sense. It is entirely possible that in a future civilization, an Elon Musk, or Koch Brother, or Justin Trudeau, is playing a highly technical game of Second Life and we are but background NPCs. I suppose I don't have a very concrete way of debating this idea other than that it is 1) boring and 2) depressing. I and other people like me find it much more likely that we live in a simulated world with one or two key changes from our programmer's world. Maybe we're the simulation where a fascist dictatorship rose in power in 1940's Germany. Or we're the simulation where replaceable parts were invented in the 1800s. Maybe In our programmer's world England is a communist superpower and Churchill wrote a manifesto instead of Marx. There are a nearly infinite number of historical what-ifs and changes to simulate and observe that make it more likely a given simulation involves hypothetical alterations. Or maybe we're the simulation where nuclear fission is weaponized or where the greenhouse gas effect is magnified. A lot of people really sold on Simulation Theory lie in a camp that can be explained as the intersection between Bostrom's Scenario 3 and Scenario 1 or 2. In other words, while Scenario 3 is the most likely, it is used primarily as a tool to explore scenarios 1 and 2. A great deal of academic knowledge could be gleaned from learning how hypothetical past Earths handled certain events. Would income inequality exist if we simulated an Earth that was forced to deal with an amplified version of it and learned from it's actions?

You live in a simulated universe, and so what?

At South by Southwest 2019, internet mogul George Hotz gave a talk about "Jailbreaking the Simulation". Early on in his talk, he mentions how certain players of the classic video game Super Mario World have learned how to program entirely different games into Super Mario World. By placing shells and "?" blocks in certain positions, new, original code can be executed in-game to warp around the cartridge's memory or just play Snake. Hotz then goes on to extend this idea to a simulated universe we live in. Essentially, he posits "What if we were Mario in Super Mario, and became aware that it's possible to place blocks in specific positions to unlock hex editors and so on and so forth?". People like Hotz want to apply Simulation Theory to solve problems with supernatural methods and "break out". I don't want this. I think the knowledge of definitively proving whether or not we live in a simulated world should be a goal in and of itself. We don't need to break out or "jailbreak" ourselves to be "truer" than we are now. How would your life change if, tomorrow, Dr. Gates proved beyond a shadow of a doubt that the fundamental forces of nature are computer-generated? Honestly, it wouldn't. Knowing so would be nice, but won't change how mustard tastes.

Like I said at the top, this thread is mostly an attempt at promoting discussion about a topic I'm pretty interested in. Even if the great wall of text turns people off from engaging, it was a nice excuse to organize my thoughts into one place. I'd be more than happy to clarify anything I might have explained poorly or answer your related questions to the best of my ability. Thanks for reading!

This post isn't an attempt to sway others' opinions or "convert" anybody. If anything this is more of a personal exercise that I hope to make something constructive out of and possibly promote discussion with. Before we begin, I'll disclaim that I am not an expert. In anything. (except maybe masturbating). I studied chemistry for 2 years at a popular state university and now I study accounting. So, if you want to read more about Simulation Theory or share your thoughts/ideas, I'd love to talk, but keep in mind this isn't super-serious and I'm not qualified to explain high-concept math or science concepts.

You can find a lot of discussion on Simulation Theory on the internet but I don't consider it all to be very productive. For example, some of the top posts on the subreddit r/simulationtheory are memes about eating silica packets, paint jobs that makes cars and buildings blend into the environment, and two ceramic busts that look like the meme of the boy following the girl around with a trumpet. Am I wrong for trying to find serious discussion of Simulation Theory on Reddit, or is the public at large simply not interested in entertaining the thought? The answer is probably both, but I don't see why it has to be that way. The document responsible for most Simulation Theory discussion today was published in the journal Philosophical Quarterly in 2003 and outlines the basic argument for why it is more likely than not we live in a simulated universe. You can read the full paper by Nick Bostrom here , but I'll summarize the argument below:

Why are you living in a simulated universe?

Bostrom's paper argues that one of the 4 possibilities must be true:

Scenario 0: Humanity never develops the capability to run hyper-realistic simulations

Ok, I cheated a bit because Bostrom doesn't seriously discuss this scenario, though it is commonly included in modern discussions of Simulation Theory. Simply put, this scenario suggests that it's impossible that any computer ever could fully simulate an entire world with the precision we observe now. Most people agree that this scenario is fairly unlikely. When looking at the strides computing power has taken in the past 20 years alone, it isn't a far cry to think that lifelike global simulations could be possible in the a few decades' time. Moore's Law states that every 18 months, processor speeds double from their capability 1.5 years ago. A processor the same strength as one made 18 months prior will cost half as much to manufacture, according to this rule, and the very cutting edge of computing should quadruple in strength every 3 years. The advent of Quantum Computing may even throw Moore's Law out the window as bytes go from being 1's and 0's to being a value along an entire spectrum, and herald a growth in computing power akin to the industrial revolution's impact on manufacturing technology.

Scenario 1: Humanity is capable of developing simulation technology, but goes extinct before being able to fully utilize it

This possibility gains more and more traction every year as reports of climate change and increasing global conflict grow more frequent. Bostrom, with some humor, devises a formula he calls DOOM to try to quantify the likelihood of scenario 1. He doesn't fully discount this possibility, and even goes as far as to suggest that "mechanical bacteria ... nanobots, designed for malicious ends, could cause the extinction of all life on our planet." Grim, but I like where his heart is at. My money for scenario 1 is on climate change though and if I had to choose another theory for humanity's technological future, the "doomer" in me would say we're likely to go kaput as a species before anything truly amazing happens. Regardless, there's no evidence yet that global extinction is more possible than the alternative, so the logical mind has to move on to another theory.

Scenario 2: Humanity is capable of developing simulation technology, but isn't really interested in using it

Similar to scenario 0, this one is simply not probable. The concept of "convergence" explains why it is much more likely that civilizations would want to run ancestor simulations than not. Looking at the popularity of simulation games like The Sims, a future civilization would have to converge together to be completely unlike us and not find simulated beings interesting. Another possible "convergence" is that the cost of running such simulations would be prohibitively expensive, but between the increasing number of millionaires the money to fund simulations shouldn't be hard to come by. It isn't unreasonable to think that highly advanced simulations could have military applications, and if this type of simulation was quite expensive for some reason, I'm sure America's defense budget could make room for it. On top of this, all it would take is 1 computer to simulate our entire world. Therefore, to completely avoid this hypothetical single computer to run an ancestor simulation, there would have to be a global convergence of culture that would make it unlikely or impossible. Perhaps an advanced civilization has a moral objection to running simulated worlds. Well, even if this were true, this civilization would also need some way to completely outlaw morally objectionable activity.

When you think about cultural convergences as the only reason why an entire global civilization couldn't or wouldn't want to run ancestor simulations, scenario 2 becomes much more unfavorable. There simply isn't a historical precedent to suggest that a future world would converge to one mind set and disagree with something so fundamentally interesting to us now.

Scenario 3: Humanity is capable of developing simulation technology, and uses the hell out of it

Now we get to what Bostrom describes as "conceptually the most intriguing" scenario, and the reason why I'm here typing this out in the first place. Most believers in Simulation Theory say something along the lines of "it's more likely that we live in a simulation than not" or "most evidence that we live in a computer simulation can't be disproven as of yet". If an advanced society became capable of running ultra-realistic simulations, they would create far more simulated worlds than they would have real worlds. Therefore, the most probable reason for any given person's existence would be because they are a simulation, given the raw number of simulated people vs. "real" people. It's important to note that Bostrom ends the paper saying that "In the dark forest of our current ignorance, it seems sensible to apportion one’s credence roughly evenly between" the three main scenarios. If you seriously debate the likelihood that you live in a simulated world, then you must also seriously debate the opposite. The scientific approach doesn't seek to fit the world into a pre-determined idea, but rather formulate ideas that explain why we see what we see. In other words, we look for a box the universe fits into, not to cram the universe into a box we already have. With this in mind, I want to move onto observable and measurable phenomenon that would be explained by Simulation Theory.

You are living in a simulated universe, and why.

The first example I'll give of something that can be explained by Simulation Theory is something many people have become familiar with thanks to high school physics, but I'll give a refresher on just in case you've forgotten

This is the formula for calculating the gravitational pull that 2 objects have on each other:

This is known as an "inverse square law", which basically means the magnitude of the force is determined by the square of the distance between the two relevant objects/bodies. Want to know the gravitational pull between the Sun and Earth? Easy, just calculate their masses and multiply them together, then divide by the distance between them, squared. In order to get a unit of measurement that actually makes sense, the constant G is used so that you end up with Newtons as your unit. According to this formula, your left boob and the planet Jupiter have a gravitational pull on each other, but of course this pull is tiny because the distance between you and Jupiter, "r" in this case, is veeeery large, and the mass of your left boob is veeeery small (m) compared to the mass of Jupiter (M).

Hopefully you're following along so far. Now I'm going to show you the formula for determining the pull that two charged particles have on each other. Called "Coulomb's Law", this formula can be used to find out how strong of a pull an electron and a proton have on one another, or how strong of a pull two oppositely charged magnets have on each other. Thinking about this law in terms of magnets is actually quite useful for understanding the important difference between Coulomb's Law and gravity. The determining force here is NOT GRAVITY, since the pull that two magnets have on each other is really just decided by their strength and not their size. Two magnets can have a very strong pull but be very small. So we know that the size ("m" or "M") of charged particles is not relevant for deciding how strongly attracted they are. It's really just the magnitude of their charge.

This is Coulomb's Law:

Look familiar?

It's also an inverse square law, just like the force of gravity. But unlike the force of gravity, this equation is used to determine how strong the force is between two charged particles, like electrons. Just like how the pull between planets and physical objects drops off as their distance increases, so too does the force exerted by two charged objects drop off as they move farther away, and at the exact same rate. So why do the planets orbiting the sun and the electrons flowing through your motherboard behave in the same way, despite being compelled by different forces? One solution could be that Coulomb's Law is being used to crudely approximate gravity for us in a simulated world.

Another observable quirk that would be explained by us living in a simulation is Fermi's Paradox. Fermi's Paradox basically states that: if the universe is billions of years old and contains a seemingly-infinite number of planets, then it must also contain a seemingly-infinite number of life-bearing planets. Then why have we not been in contact with any of them? This paradox can be reasonably explained by a number of things, such as the unfathomable distance between our solar system and others coupled with the limitations of traveling near the speed of light. But still, all reasonable calculations result in estimates of interstellar colonization taking significantly shorter time than the current life of the universe. If we lived in a simulated world, there wouldn't necessarily be a need to simulate alien life outside of Earth, especially if we live in a simulation meant to test the hypothetical impact of various global events.

Even at the cutting edge of theoretical physics, the idea of Simulation Theory has taken hold of top academic minds. The 2016 Isaac Asimov Memorial Debate, moderated by Neil DeGrasee Tyson, was centered around the question Do We Live in a Computer Simulation? During this debate, James Gates shares some of the findings of his research. This clip is of Dr. Gates talking about finding error-correcting codes in natural particles while using the Large Hadron Collider. If you understand computer science pretty well, my friends tell me it's pretty interesting, but the jargon is a little too technical for me to fully follow. You can find the full debate here if you have a spare couple hours and want to listen to very smart people talk about this topic at great length.

You live in a simulated universe, but why?

Almost everyone is familiar with the concepts of means, motive, and opportunity in relation to criminal justice. In order to have a slam-dunk prosecution, you need to identify how, why, and when a defendant would have committed a crime. A lot of the casual conversion surrounding Simulation Theory revolves around our world being some sort of computer game. I really don't like this idea for a couple reasons, mostly because the motive doesn't make much sense. It is entirely possible that in a future civilization, an Elon Musk, or Koch Brother, or Justin Trudeau, is playing a highly technical game of Second Life and we are but background NPCs. I suppose I don't have a very concrete way of debating this idea other than that it is 1) boring and 2) depressing. I and other people like me find it much more likely that we live in a simulated world with one or two key changes from our programmer's world. Maybe we're the simulation where a fascist dictatorship rose in power in 1940's Germany. Or we're the simulation where replaceable parts were invented in the 1800s. Maybe In our programmer's world England is a communist superpower and Churchill wrote a manifesto instead of Marx. There are a nearly infinite number of historical what-ifs and changes to simulate and observe that make it more likely a given simulation involves hypothetical alterations. Or maybe we're the simulation where nuclear fission is weaponized or where the greenhouse gas effect is magnified. A lot of people really sold on Simulation Theory lie in a camp that can be explained as the intersection between Bostrom's Scenario 3 and Scenario 1 or 2. In other words, while Scenario 3 is the most likely, it is used primarily as a tool to explore scenarios 1 and 2. A great deal of academic knowledge could be gleaned from learning how hypothetical past Earths handled certain events. Would income inequality exist if we simulated an Earth that was forced to deal with an amplified version of it and learned from it's actions?

You live in a simulated universe, and so what?

At South by Southwest 2019, internet mogul George Hotz gave a talk about "Jailbreaking the Simulation". Early on in his talk, he mentions how certain players of the classic video game Super Mario World have learned how to program entirely different games into Super Mario World. By placing shells and "?" blocks in certain positions, new, original code can be executed in-game to warp around the cartridge's memory or just play Snake. Hotz then goes on to extend this idea to a simulated universe we live in. Essentially, he posits "What if we were Mario in Super Mario, and became aware that it's possible to place blocks in specific positions to unlock hex editors and so on and so forth?". People like Hotz want to apply Simulation Theory to solve problems with supernatural methods and "break out". I don't want this. I think the knowledge of definitively proving whether or not we live in a simulated world should be a goal in and of itself. We don't need to break out or "jailbreak" ourselves to be "truer" than we are now. How would your life change if, tomorrow, Dr. Gates proved beyond a shadow of a doubt that the fundamental forces of nature are computer-generated? Honestly, it wouldn't. Knowing so would be nice, but won't change how mustard tastes.

Like I said at the top, this thread is mostly an attempt at promoting discussion about a topic I'm pretty interested in. Even if the great wall of text turns people off from engaging, it was a nice excuse to organize my thoughts into one place. I'd be more than happy to clarify anything I might have explained poorly or answer your related questions to the best of my ability. Thanks for reading!

Your support makes Blue Moon possible (Patreon)

Your support makes Blue Moon possible (Patreon)